When you arrive in Lodwar, the capital of Turkana County, the contagious smiles, loud chatter, clean carpeted roads owned by vrooming boda boda motorcycles and motor vehicles can have you fooled to believe that it is a depiction of the life in the entire county.

Branch for a kilometre or two off the main highway and the tarmac terminates abruptly and we are henceforth painfully embraced by a rough sandy winding road that cuts through the penurious lifestyle of the rural folk of Turkana County and their sparsely spread huts, offering a sneak peek into the secrets of Kenya’s largest county.

The cradle of mankind we call it. The land that offers some of the most breathtaking sceneries and historic sites that attract many tourists and archeologists alike. However, beneath the beauty lies a pressing problem. Malnutrition. After a rough ride of close to 45km, we arrived at Kerio Ward in Turkana Central Constituency, the desperation captured in the screams from hungry children and murmurs from their resiliently patient mothers welcome us here.

I find a shed that acts as an outreach camp, and it is fully packed as tens of women and their young ones of varied ages wait for nutritional assistance, but most importantly medical attention from donor-funded NGOs in collaboration with community workers and groups.

The women, including those who are pregnant and others lactating, have trekked in the scorching sun from the nearby villages, mostly on empty stomachs, and they sit on the sandy ground and wait patiently for their turn to be called to bring their babies for nutritional, medical and other essential checks before the best interventions are prescribed.

Read More

Many have not had any meal for hours, some even days, and their stares pierce through the cartons stacked nearby containing pellets of the Ready To Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) donations, which are given to the mothers and their children during the outreach.

The situation is dire, even with the outreach programme spearheaded by Save The Children, Turkana County government and other local and foreign organisations amid concerns over the planned scaling down of such efforts due to financial constraints caused by reduced donor support, leaving the lives of many women and children who rely on such critical initiatives in limbo.

Among those who have come for the outreach is Sarah Namwar Eregae, a mother of three children aged eight, three and two, who are all beneficiaries of the essential programme by Save the Children and they receive nutritional commodities and monitoring of their vitals.

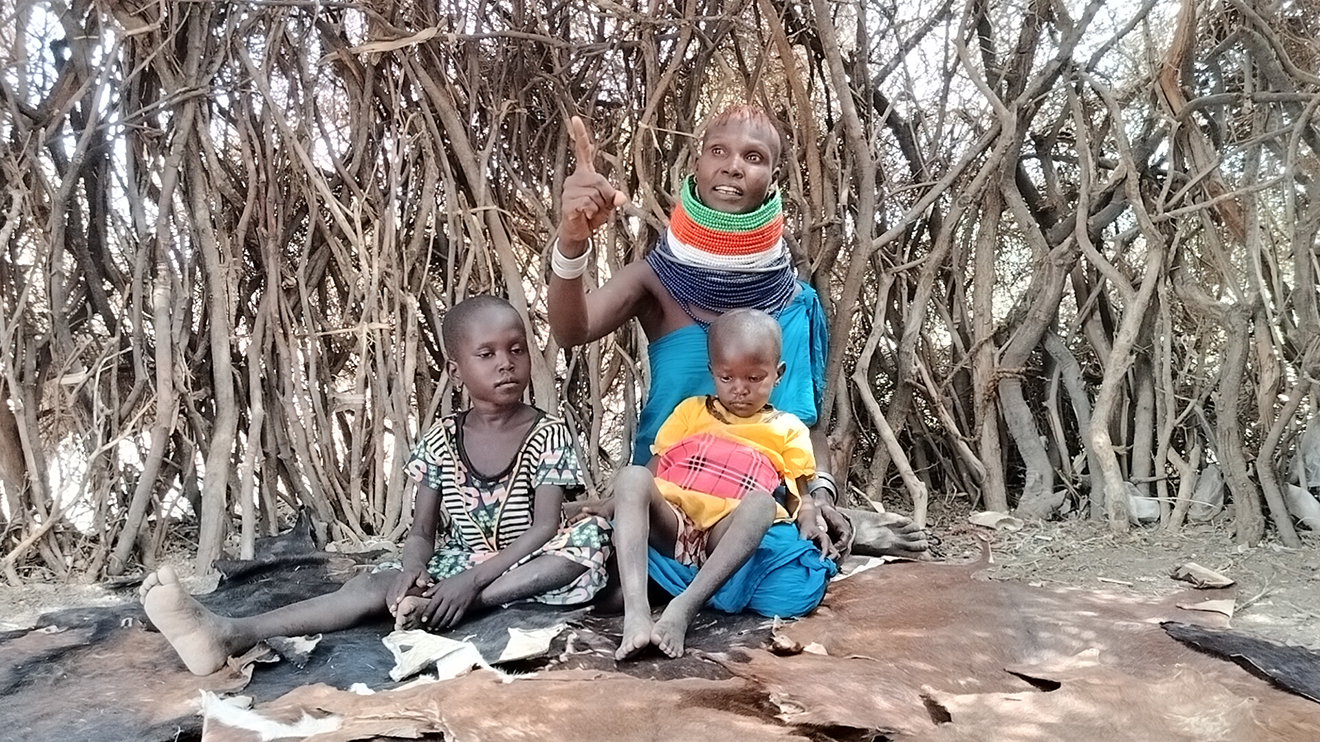

Sitting down moments later with Eregae and her children in her hut made from sticks tied firmly together, the 31-year-old tells me that her larger family of nine members used to rely on basketry to eke a living but during such long periods of drought and hunger they are forced to rely fully on the outreach programmes to overcome the emergent nutritional challenges, especially for her children.

“The outreach helps my family a lot because due to this drought most of the children in Kerio village became severely malnourished, including my own. My children receive nutritional commodities every two weeks and they are able to eat for those few days,” she tells me.

Sarah paints a gloomy picture of her life, and that of her children in a situation where they might be forced to fend for themselves in the bare lands if the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that come to their aid every fortnight cut back their interventions.

“Without the outreaches it is difficult to survive here, not just for my own children but also the other children. The outreaches also help in accessing treatment for diseases like malaria and diarrhea which are now common in my village. The nearest health facility is too far away, like 8km, so when you or your child is sick you cannot even contemplate walking with the little energy you have. I hope the organisations that support our community continue with the outreaches,” she narrates.

Initially, when Lake Turkana waters were close to the fishing village of Kerio, they used to supplement their diets with fish but the long ravaging droughts has seen the lake recede 15km away. The sorghum donations they used to receive from well-wishers also stopped.

“Now, with the outreaches, at least the children can get something to eat, even if it is only two times a month. Without it all of us will suffer at the family level, both children and adults, and that is not good,” she says as her voice changes not wanting to fathom such a scenario.

According to the June 2022 SMART (Standardized Monitoring and Assessment of Relief in Transition) survey, 27 per cent of children in Turkana Central were found to be acutely malnourished, which is alarmingly way above the World Health Organisation (WHO) threshold of 15 per cent for emergencies, and are in need of urgent interventions.

“I know in Kerio, Save the Children was supporting us with 22 outreach sites. We hear they want to scale them down to 11. We see the impact that people have received from these outreaches, but if they are reduced to 11, where will the rest go? The county cannot do it alone. Is there a way this can be retained then we can mobilise resources and our people can get these services?” posed Jane Atabo, a Sub-County Public Health Nurse in Turkana Central.

In the integrated outreach centers, severely malnourished children are given the RUTF, moderately malnourished put on a dietary plan while pregnant women are given the unimix. The prominent ribs and visible shoulder blades on most of the children is indicative of just how important the interventions by the nutrition experts from the Save The Children are.

Nickson Lomuse, a project officer with local NGO Sapcone, says their emergency interventions in Turkana Central came following the failure of four consecutive rainy seasons leaving all water sources dry, pastures depleted and all their livestock dead.

“When we started the programme in September 2022, we had very high malnutrition caseloads at 27 per cent, which is almost double the 15 per cent WHO threshold for emergency. We had to partner with Save the Children to develop this emergency health and nutrition programme so that we are able to reach those hard-to-reach communities, especially the vulnerable women and children, who really bear the brunt of drought in Turkana County, especially in Kerio ward,” Lomuse tells me.

The integrated emergency health and nutrition outreach programme, which is a partnership between Save The Children, Sapcone and Turkana County Government’s Ministry of Health, is availed to mainly pregnant and lactating women and children under 5 years old in the ward, with the adult residents also educated on the adoption of family planning methods.

“Now with reduced funding, we will continue to leave more children and mothers suffering because key facilities are located far away and these communities are migratory. We really appeal to all donors and all funding agencies who might be in a position to support these communities to continue to support these health, nutrition and WASH programmes to help these vulnerable communities," Lomuse appealed.

The badly needed outreach programme currently covers only 22 out of 80 sites in the vast Turkana County and reduced funding means the scaling down of such services to even fewer sites leaving the locals at the mercy of the vagaries of the adverse effects of climate change.

As we drive away from the Kerio outreach site back to Lodwar, I cannot help but wonder what prospects the future holds for the women and children I have left behind should the essential assistance be forced to scale down.

The following day, and a 177km drive on mostly rough long meandering roads cutting through countless dried-up rivers and an overkill of vivid evidences of the high poverty levels in the rural Turkana County later, we arrive at Kachoda in Lokitaung, at a site christened Number 1.

The situation in Kerio is replicated here and we are welcomed by the persistent cries and screams hunger and malnourishment from a shed filled by tens of women and their children each waiting for their turn to assessed and given a few pallets of RUTF and medicine, where applicable. The outreach center saving the women and children from the previous long treks.

Here we meet 33-year-old Amejen Loweet Lokwami, a mother of two who is also six months pregnant. For her, the integrated outreach at Kachoda has shortened her 20km treacherous regular journey on the scorching sun and dusty roads through the forests from her Kabarait village home to the nearest health facility to access antenatal care.

“My children have benefitted immensely from the outreaches. The nutrition experts there screen them and whenever they are found to be malnourished then they are introduced into the nutrition programme where they receive supplements to get them back to normal. As a pregnant woman, they also give me folic acid and medicines and they have cut short the long trip I used to make to access antenatal care,” says the resilient Lokwami.

Woe unto her if she needs urgent medical attention in between the outreach programmes as she is forced to leave her children either alone or under the care of a neighbour before embarking on the long painful trek.

“If I experience any issue with my pregnancy that needs medical attention within the two-week period between the outreaches, I have to trek for close to 20km. I set off on such a trip as early as 7am and the earliest I can reach the nearest health facility is at 11am, and being expectant means I have to pace myself too,” she expresses uncomfortably.

Priscilla Akal, a nurse from Kachoda Dispensary who is also part of the outreach, reveals that malaria, upper respiratory tract infections and diarrhea lead the diseases that affect the children under five who visit the health facility, as well as snake bites, requiring their urgent intervention.

Simon Emejanai Tiir, an outreach assistant at Save the Children, knows too well the importance of their interventions and reducing the distances for the women and children.

“The key factor here is the distance; the people in this community find it hard to access the health services, the nearest facility from here is about 9km. we are providing curative services. Malnourished pregnant and lactating mothers and children are identified and admitted into the outpatient therapeutic programme,” Tiir narrates.

He warns, “If a scale down occurs, if we exit this place, these beneficiaries will find it hard to access these healthcare services because this is really w3hat they depend on. Our availability in this place means a lot to them. If we pull out, they are the ones who will be at a disadvantage.

Turkana County’s Ministry of Health and other stakeholders approved a SMART survey report conducted in January 2023 to the tune of Sh9.7 million in a bid to improve the nutritional status coverage in the county and reduce deaths resulting from malnutrition.

Speaking during the validation exercise in Lodwar, the Chief Officer for Preventive and Promotive Health, Peter Lomorukai, said the latest survey will provide adequate information for even intervention.

The SMART survey follows a severe drought that is still ravaging most part of Turkana County necessitating food, health and nutritional intervention to improve outcomes for the resident.

Malnutrition is lack of proper nutrition, caused by not having enough food to eat, not eating enough of the right nutritional requirements, or being unable to use the food that one does eat.

.jpg)

The two case studies are just a drop in the ocean as tens of hundreds of other children suffer from malnutrition, which is prevalent in the vast Turkana County, whose Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) level among infants and young children has recently fallen in the range of 15.0 - 29.9 per cent. According to WHO, the severity of malnutrition is only acceptable if the prevalence is less than 5 per cent while a GAM value of more than 10 per cent is tantamount to an emergency, yet Turkana County’s has in the recent years teetered between 15 and 30 per cent hence the need for constant monitoring and urgent interventions.

For a human body to remain well nourished, it needs a balanced diet that incorporates proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals from different food groups. However, 9 in 10 residents of Turkana County are not in a position to afford three square meals a day as the poverty levels stand at 94 per cent, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS).

-1730442410.jpg)

(1)-1730070935.jpg)

(1)-1727972556.jpg)

-1728654105.jpg)

(1)-1730745141.jpg)