A new report has revealed that Kenya is quietly bleeding an estimated Sh23.2 billion annually through illicit gold exports, with smuggled consignments outweighing the country’s declared shipments by several tonnes.

While government records suggest a modest 672 kilogrammes of gold exports in 2023, import data from recipient nations tells a dramatically different story, indicating imports from Kenya soared above 9.6 tonnes in the same year.

The discrepancy, uncovered by SWISSAID, highlights Kenya’s dual identity as both a mid-tier gold producer and a regional smuggling corridor, with much of the metal funnelling through to Dubai.

According to the report, “The mine has produced circa 1 tonne of gold during this period [i.e. between 2010 and 2020]”, adding that “we are small-scale and produce circa 300 kg a year”.

This admission by Maris Group CEO Charlie Tryon regarding operations at Karebe, Kenya’s largest producing mine, underscores the country’s under-reported gold capacity.

Read More

Artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM), who dominate the sector, operate in the shadows, with virtually none of their production captured in government records.

A government-backed estimate from 2019 placed ASM output at 6.9 tonnes per year.

“Most of the ASM gold is never recorded in government books because it is either traded by unlicensed dealers internally or smuggled to neighbouring countries through the porous borders. As such no data on gold from ASMs as of now,” one expert explained.

Adding to the complexity, Kenya has become a crucial transit route for gold smuggled from conflict zones including South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

“About 100 to 200 kilogrammes of illicit gold from the DRC leaks into the Kenyan secondary market every month,” a smuggler told researchers.

This alone could amount to 2.4 tonnes annually, with an estimated market value of over Sh13.6 billion.

Despite Kenya not being a major consumer of gold, it continues to import the precious metal. Official data for 2023 records only 385 kilogrammes in imports, yet Emirati authorities list gold exports to Kenya that vastly exceed this amount.

“The gold from Oromia and Southern Ethiopia is smuggled out of the country via Kenya’s and Somalia’s borders,” an Ethiopian journalist reported.

At the heart of Nairobi, Eastleigh has become a nerve centre in this opaque trade, where Somali and Indian traders dominate the market.

“This business is mostly dominated by Indians and Somalis (of Kenyan origin) and their wholesale shops are in Eastleigh,” an expert stated.

A cargo containing three tonnes of gold reportedly vanished from Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in November 2023, a disappearance pointing to complicity at higher levels.

The government has acknowledged the chaos and is inching towards formalisation.

“The bulk of gold production in Kenya is usually done by small-scale and artisanal miners in Western Kenya, […]. However, since the gold is traded informally this is never reported in government statistics […],” states the National Action Plan for Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining (2022).

However, efforts to license miners and monitor refineries remain at what one expert described as “infant stages”.

As of early 2025, a proposed Gold Processing Bill—seeking to centralise refining under a new state-run corporation—awaited enactment.

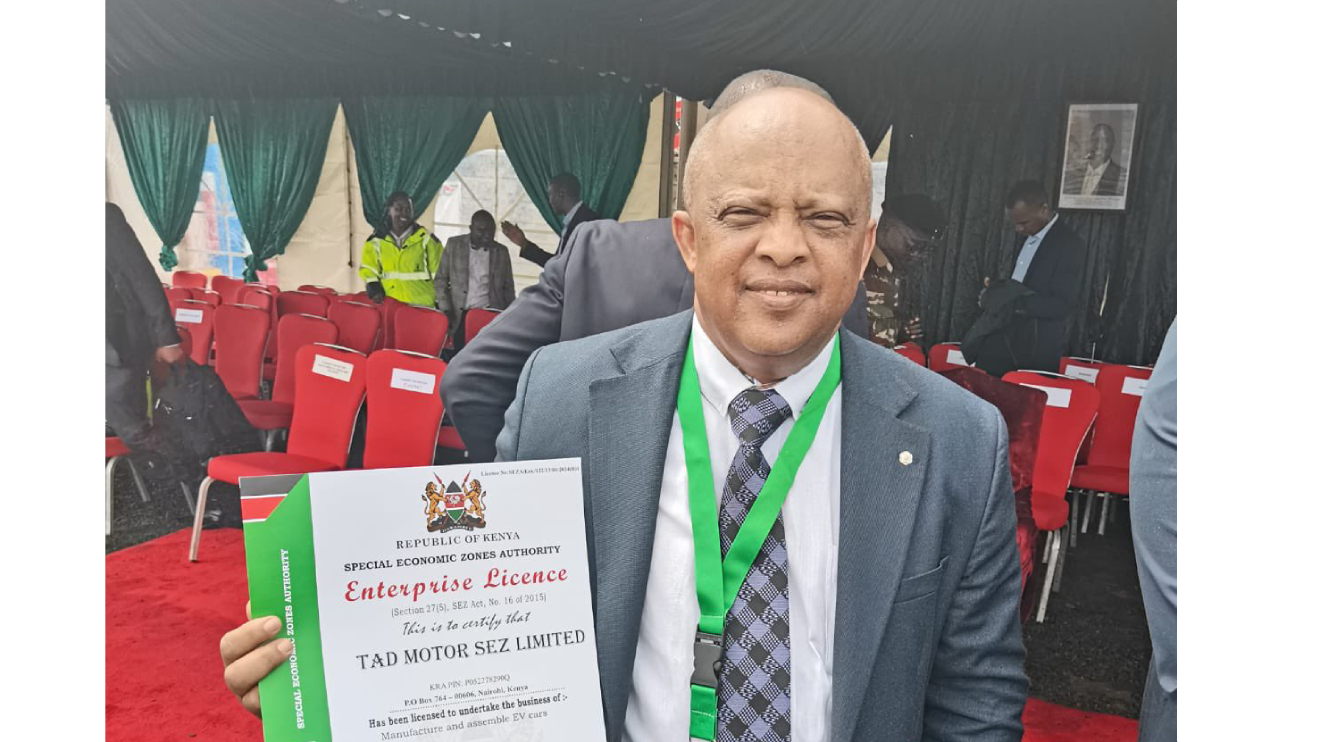

Parallel to this, the opening of the largest gold market in East and Central Africa at Eastleigh’s BBS Mall aims to entice legitimate dealers.

“The largest gold souk in East and Central Africa,” it was billed, with government officials urging traders to get licensed.

Nonetheless, scepticism remains. Attempts to trace gold flows to their destination have been stymied by missing, inconsistent or clearly manipulated data.

For instance, Kenya’s reported gold exports to Switzerland in 2021 stood at 134 kg, while Swiss authorities reported receiving 247 kg.

“Due to a lack of proper structure, prominent smuggling, and lack of proper implementation of record keeping in the ASGM mines and royalty collection, the data is not easy to aggregate," the Kenya Chamber of Mines admitted.

With conflicting data and rising volumes of gold flowing through informal networks, it remains unclear whether proposed reforms can rein in a black market that now eclipses Kenya’s legitimate gold trade.

The true scale of the country’s gold wealth may lie not in government ledgers but in the hands of traffickers moving bullion through shadow routes that span borders and continents.

-1749112138.jpeg)